Creating technical documentation content is a challenging and multifaceted process that involves many departments within a company. Technical writers, marketing, development, and other departments all contribute to generating information which is then condensed into usable content for end users. However, due to the complex and intricate nature of the process, identifying areas for improvement can be a challenging task. This is where Design Thinking comes into play as a powerful problem-solving methodology. We'll explore how it can help unlock creative solutions for optimizing technical documentation processes, with examples taken from the case study performed for my master’s thesis.

Why Design Thinking?

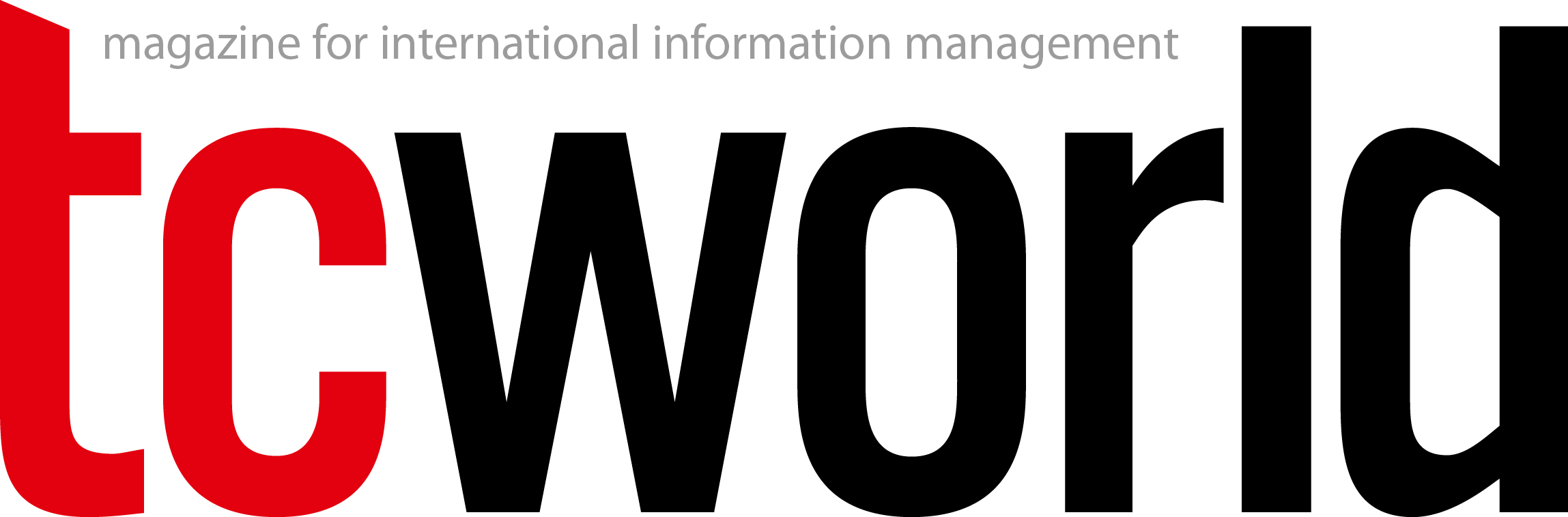

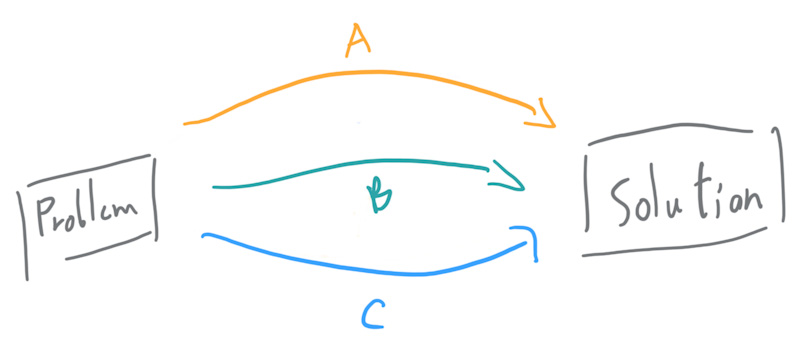

Problems are often sorted into three kinds: simple, complex, and wicked. For simple problems, both problem and solution are well-defined with only a few choices to be made along the way. Complex problems might have several facets on both the problem and solution sides. The path may also not be as clear, but still, the overall scope is well-definable. Wicked problems, on the other hand, combine a complex environment with a fuzzy scope and thus require a more explorative approach.

Figure 1: Simple, complex or wicket? Different problems require different solutions.

This need for creativity, exploration, and iteration makes wicked problems perfectly suited for Design Thinking, although the approach of course also works well for the other two problem types. For a great introduction to Design Thinking mindset and its history, I strongly recommend Change by Design by Tim Brown. [1]

Project setup and Design Brief

To apply Design Thinking to the technical documentation creation process, it was necessary to adapt the concept a bit. The Design Thinking method is primarily described and designed for creating novel products or business models. To apply this approach to my scenario, the viewpoint was changed from being a department within the organization to becoming a technical communication service provider within the company. This mindset made it easier to conceptualize new ideas as user-centered product or service concepts.

To guide the process in my case study, I relied mainly on The Designing for Growth Field Book: A Step-by-step Project Guide by Ogilvie et al. [2] This framework is based on four key questions:

- "What is?"

- "What if?"

- “What wows?"

- "What works?"

By working through these questions step by step, I was able to develop a structured approach to the Design Thinking process and apply it to my case. Of course, there are many other resources about Design Thinking, and I refer to a few in the following.

The first step of this framework is to define your project area and to draw up the Design Brief, which is the document that will guide your design process by ensuring that the results stay aligned with the goals and questions defined in the Design Brief. Your Design Brief will contain a project description, scope, key constraints (time, budget, resources), and requirements along with metrics and desired outcome.

The second key document to create in this step is your People Plan, to define the key stakeholders to be addressed in the design process. This will make sure you keep the focus on designing a solution for your specific audience.

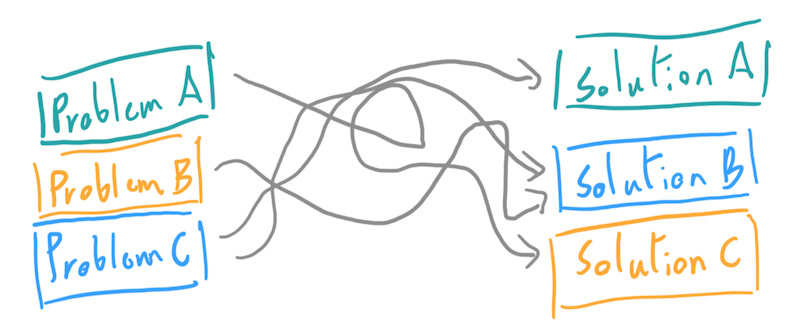

Figure 3: Step by step through the Design Thinking process

Step 1: Getting inspired

The first step in the Design Thinking process is to analyze the current state of things. Here, Design Thinking doesn’t diverge much from a classical approach, yet knowing your starting point is key for any kind of development. Moreover, by taking a deep dive into the problem area, this step will spark the ideas we need in the brainstorming phase.

In my approach, I decided to base my analysis on three pillars:

- A process analysis: taking the time to update my process map and chart out every detail

- A portfolio analysis: clearly defining the scope of my document creation to identify all stakeholders and dependencies

- A survey with my stakeholders: Test key assumptions and get input from my internal customer base

Portfolio and process analysis

The portfolio analysis revealed that the scope of technical customer documentation is extensive and includes documents related to marketing as well as highly technical ones. Typically, most products require multiple documents, such as product manuals and technical datasheets. So, with only a team of two responsible for technical documentation creation, the need for an efficient process becomes evident to keep up with the pace of product development and updates.

The analysis of the technical customer documentation creation process using BPMN 2.0 revealed a high level of complexity due to the involvement of various parties. Additionally, the presence of documents in Word format added to the intricacy of the process, requiring extra effort to manage them effectively. However, a process map alone does not provide a complete picture of the process, as it fails to show the number of loops and time spent in some steps. My experience is that some documents can get stuck during steps outside of the technical documentation department, causing delays in the process.

These two analyses sparked some first ideas, so I created a survey to confirm or refute my assumptions.

The survey

The big advantage when targeting internal customers is that your target group is easily found, as we have already defined our stakeholders in the previous step. The sample was selected to include all colleagues who have been in contact with the technical customer documentation process in any way (e.g., providing input, reviewing documents, or also requesting documents from the team).

To optimize engagement and minimize dropouts, it was important to design the online survey questionnaire to be as simple as possible and easy for participants to complete. The question format was chosen based on the type of information to be retrieved. Closed-ended questions with yes/no options or multiple-choice questions were used for most questions, while Likert scales were used for rating questions. Some qualitative questions were designed as open-ended questions to allow for in-depth feedback.

Below are a few questions that provided the most valuable insights:

- Do you know where to find the currently released technical customer documentation?

- Do you know whom to ask for creating and updating technical customer documentation at Polytech?

- If you are (or have been) involved in the technical customer documentation process, what is your opinion of the following aspects of the process?

- Process transparency

- Process management

- Communication in the project

- Completion time

- Communication channels (email, JIRA, meetings, ...)

- Clarity of responsibilities

- What can we improve in the technical customer documentation creation process?

- If you are involved in the review process of technical customer documents, which communication channel(s) do you prefer?

- What is your opinion of the following aspects of the deliverables (manuals, datasheets, etc.)?

- Quality

- Completeness/appropriate scope

- Correctness of information

- Comprehensibility and readability

- Consistency and standardization

- Availability (when and where it's made available)

- Compliance

- Delivery format, layout, and design

The survey results showed that the current state of the deliverables met the company's expectations, with only 1.7% negative responses overall. However, process aspects had a 12% negative response rate overall, with completion time and clarity of responsibilities being the biggest issues. The survey also revealed other communication issues, especially in the open-ended questions. For example, several survey participants commented that the technical documentation department should get involved sooner in the development process. These findings confirmed many of the assumptions I had made during the design project setup and became the focus of subsequent design steps.

Design Criteria

Based on the analysis of the current state, Design Criteria were defined to guide the following process:

- The stakeholder has a clear picture of his involvement in the technical customer documentation process and how to interact with it.

- The stakeholder has an overview of the other steps and other stakeholders involved.

- The stakeholder knows what to expect from the process deliverables, for example, a product manual.

The constraints and further requirements from our design brief of course still apply, but these goals are now our baseline to gauge any concept we come up with.

Step 2: Getting creative

True to the motto “What if?”, the goal of this phase is to generate creative ideas. And to have the chance for some good ones, numbers are key. We need as many ideas as possible to have the chance to find among them the one that will spark a great concept. This is why this phase is also often called the divergent phase of the process: We don’t want to think within constraints here. The constraints are sure to come back later in the process.

This is where we encountered one of the challenges of this phase: We had only just drawn up the design goals and constraints. Therefore, my recommendation is to take at least one day off between drawing up the design requirements and the brainstorming phase so that you can clear your head and think outside the box.

A few key tips for effective brainstorming:

- Eliminate group effects by having everyone note down their ideas individually before gathering or presenting them to the team.

- Stand up, move around.

- Take regular breaks in the fresh air.

- Write by hand on physical materials (sticky notes, boards …).

- Brainstorming can also be done online, but to support the above points I, personally, prefer and recommend an in-person session.

For my case, I chose the “Change Perspectives” brainstorming method. For this method, several stakeholder perspectives are defined. In my case, the stakeholders were the following:

- Research and development engineer

- Sales account manager

- Project manager

- Service and support engineer

The goal of the brainstorming session is to find ideas that address the particular needs of each stakeholder – at least ten for each (the goal of this minimum is to inspire you to think beyond the obvious few ideas). We performed four brainstorming sessions, each with a different role in mind. This exercise should come easily for professionals in the field of technical communication, as thinking from a user’s perspective is, after all, one of our key skills. Of course, there are many more methods for brainstorming, so I invite you to explore and find what works best for you.

Step 3: Concepts and pitches

Now that we have a board full of ideas, we get to the next step: Clustering ideas into concepts that play towards our design goals. Check the ideas for similarities or common solutions and gather them accordingly (this is where writing on physical sticky notes comes in handy). Now that we had a few concepts to work with, in my case, the following concepts emerged:

- Enhance collaboration with the help of a more accessible and standardized tool.

- Create a central information hub for all stakeholders where they can access information on any topic related to technical customer documentation: FAQs, process overviews, etc.

- Improve the process flow and overview for stakeholders by creating a central platform to view the current process state and dependencies of all the ongoing technical customer documentation tasks.

- Improve the distribution of content through a database accessible to all stakeholders.

For each of these concepts, you then write a so-called “napkin pitch”: Summarize in three to four key points what makes your concept fly and how it fulfills the design goals for the target users. The goal is not necessarily to present the pitches to anyone but to have you work on the arguments and thereby see the viability of your concept. If you can’t come up with anything good here, revise or discard the concept.

Step 4: Prototyping

With the concepts that made the cut of the pitches, we now enter the final stage of the design process: prototyping. Design Thinking is an inherently user-centered method, so putting our ideas out in the field is the ultimate goal. It’s important to note that prototypes don’t have to be great, and they don’t have to look nice. They can be a paper and sketch mockup for a web page on a whiteboard.

The only role of a prototype is to demonstrate the key points of your concept to your target audience – getting a quick sense of which solution looks promising and what problems or constraints might pop up. The key motto here is: Fail fast and iterate. Refine your prototype or get back to the drawing board. As tough as it might be to have to throw away a concept at this late stage – this is where the value of the Design Thinking approach is found. Don’t go forward with an idea that is not actually providing value to your customers.

In my case, the prototyping phase revealed that, for each of the three selected concepts, promising prototypes could be set up. We found the most promising results in a SharePoint prototype for the technical customer documentation process information page and a Microsoft Planner-based prototype for a central project overview. These revealed positive results within a short setup time and were met with positive feedback from users. However, the setup for a prototype for the collaboration/review concept was more difficult and had to be discarded due to time constraints.

Summary

While it may require more overhead (and thus, buy-in from management) with preparation, brainstorming sessions, and prototyping, a Design Thinking approach can lead to highly user-oriented solutions. To make the most of this approach, it is important to switch your perspective from fulfilling a specific role to thinking like a company within the company and focusing on finding convincing product or service ideas for customers. Overall, the Design Thinking approach provides a fresh and inventive way to generate solutions.

References

[1] Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. HarperCollins.

[2] Ogilvie, T., Brozenske, R., & Liedtka, J. (2014). The Designing for Growth Field Book: A Step-by-step Project Guide. Columbia University Press.

Further reading

- Kelley, T., & Littman, J. (2016). The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America's Leading Design Firm. Profile Books.

- Lewrick, M., Link, P., & Leifer, L. (2018). The Design Thinking Playbook: Mindful Digital Transformation of Teams, Products, Services, Businesses and Ecosystems. Wiley.

- Liedtka, J., & Ogilvie, T. (2011). Designing for Growth: A Design Thinking Tool Kit for Managers. Columbia University Press.

- Norman, D. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. Basic Books.