AI has brought uncertainty across many global professions, including the technical communications sector. GenAI has yet to unfold its full potential in enterprises as solutions lack trustworthy insights for large-scale decision-making. The localization industry has long been ahead of the curve when it comes to deploying AI solutions and being AI-relevant. So, what lessons does it hold for us?

Localization: Taking the scenic AI route

Of all AI challenges, language is both the oldest and newest, having experienced an AI hype cycle, an AI winter, and a second hype cycle.

Machine Translation (MT), part of Natural Language Processing (NLP), took the stage in the 1950s, fueled by the tensions of the Cold War. With the automatic translation of more than 60 Russian sentences into English, the Georgetown University-IBM experiment showed early success. However, by 1966, slow progress had stalled funding. It wasn’t until three decades later that the localization industry and Language Service Providers (LSPs) had advanced automation to attract investment. Computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools improved productivity and consistency via Translation Memory (TM), while Translation Management Systems (TMS) improved stakeholder transparency and collaboration. Later on, Statistical and Neural Machine Translation (MT) further boosted productivity, serving as powerful yet imperfect tools.

Today, Large Language Models (LLMs) are AI’s representatives in localization, illustrating both promises and risks in a market projected at US$95 billion by 2028 according to Nimdzi State Of The Language Industry forecast.

Thus, the successes and failures of AI adoption in localization hold valuable lessons for the risks and opportunities in regard to upskilling staff, quality frameworks, and data governance.

Global content workflows

Any future workflows should break both language and data barriers. The translation ecosystem has evolved through a trifecta of TM, TMS, and MT, allowing translators to focus on more complex content tasks. Beyond post-editing MT, translators guide content analysis tools, validate MT Quality Estimators (MTQE), and analyze Post-Edit Distance (PED) data to enhance both MT and human performance. This expanded role builds trust in language AI toolkits and encourages more LSP investment.

Similarly, as technical writers focus on consistency and reuse, content needs to be integrated into ecosystems that interact with AI models to provide contextual metadata for domain and audience relevance. GenAI has heightened the need for semantic frameworks to connect diverse datasets, creating opportunities for content operations specialists. In just two years, General Purpose AI (GPAI) has progressed to Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) frameworks, which enhance accuracy and offer an opportunity for technical content specialists to integrate their skills.

Simultaneously, the AI technology workflow stack is rapidly emerging, enabling the creation of scalable, layered architectures for AI operations, supported by data scientists and developers. Today’s AI ecosystem includes infrastructure, foundation models, retrieval frameworks, and integration frameworks, all of which may increasingly be surfaced by networks of more autonomous AI agents in enterprise solutions. Consequently, human oversight in content operations strategy and data management becomes indispensable.

Quality frameworks

AI/human synergies require a new quality framework. When localization stakeholders sought ways to measure MT-based deliverables, metrics like BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) compared MT to reference human translations but failed to capture linguistic nuances. TER (Translation Edit Rate) measured the effort required to bring MT output in line with human translations, but it also had its limitations as it provided only post-completion data, focused solely on edits, and excluded the research and cognitive effort of translators. As a result, neither BLEU nor TER convinced buyers or translators, as both were costly and difficult to apply in fast-paced workflows.

New frameworks became essential. The 2017 ISO 18587 standard acknowledged the growth of MT post-editing, emphasizing the importance of transparency and trust between LSPs and their clients. It noted that “no MT system can produce output equivalent to human translation; therefore, the final quality of the translation output still depends on human translators and their competence in post-editing.” The standard also established post-editing levels (full and light post-editing), helping LSPs better align with enterprise needs.

Today, language service and technology providers have adopted Multidimensional Quality Metrics (MQM). Built on earlier frameworks of the LISA QA Model and the SAE J2450, it provides a reference-free approach applicable to human, machine, and AI-generated translations. The MQM council says, “The standardized MQM approach generates structured data that reduce subjectivity, enhance comparability, and greatly improve communication and cooperation among the different stakeholders.” It can also be used, with “special considerations”, to enhance the global readiness of source content, thus potentially supporting future AI solutions.

Quality frameworks that leave room to evolve are essential. Through an iterative process, translators have developed a deep understanding of MT limitations. However, traditional quality metrics may be inadequate in an AI/human paradigm, failing to account for the synergies between AI and humans. Recognizing this, technical writers should adapt and adopt new AI-driven quality metrics, establishing themselves as quality guardians in AI-driven enterprise environments.

Collaborative reskilling

Translators are as crucial to MT workflows as they are to production workflows. Collaboration with MT developers is a challenge for translators, as MT evolved over two decades, moving the goalposts for the partnership. Early rule-based machine translation (RBMT) relied on replicating language rules and was dependent on experts to encode them. It proved complex, costly, and unscalable.

As MT technology moved toward machine learning (ML) with Statistical MT (SMT) and AI-driven Neural MT (NMT), the collaboration evolved. Developers moved away from hard-coded rules and focused instead on identifying error patterns that impacted productivity, relying on data augmentation and optimization to fix issues. Despite challenges, MT usage grew, and user feedback, based on industry use cases, improved its performance and user experience.

The translators' journey highlights the value of feedback and adaptation as MT technology reshaped their role in refining outputs and fine-tuning the dominant yet evolving MT technologies of the time. Collaborating with developers to improve tools and systems has been crucial. Technical writers can learn from translators, whose feedback has enhanced TMS and CAT tools, improving the overall ecosystem.

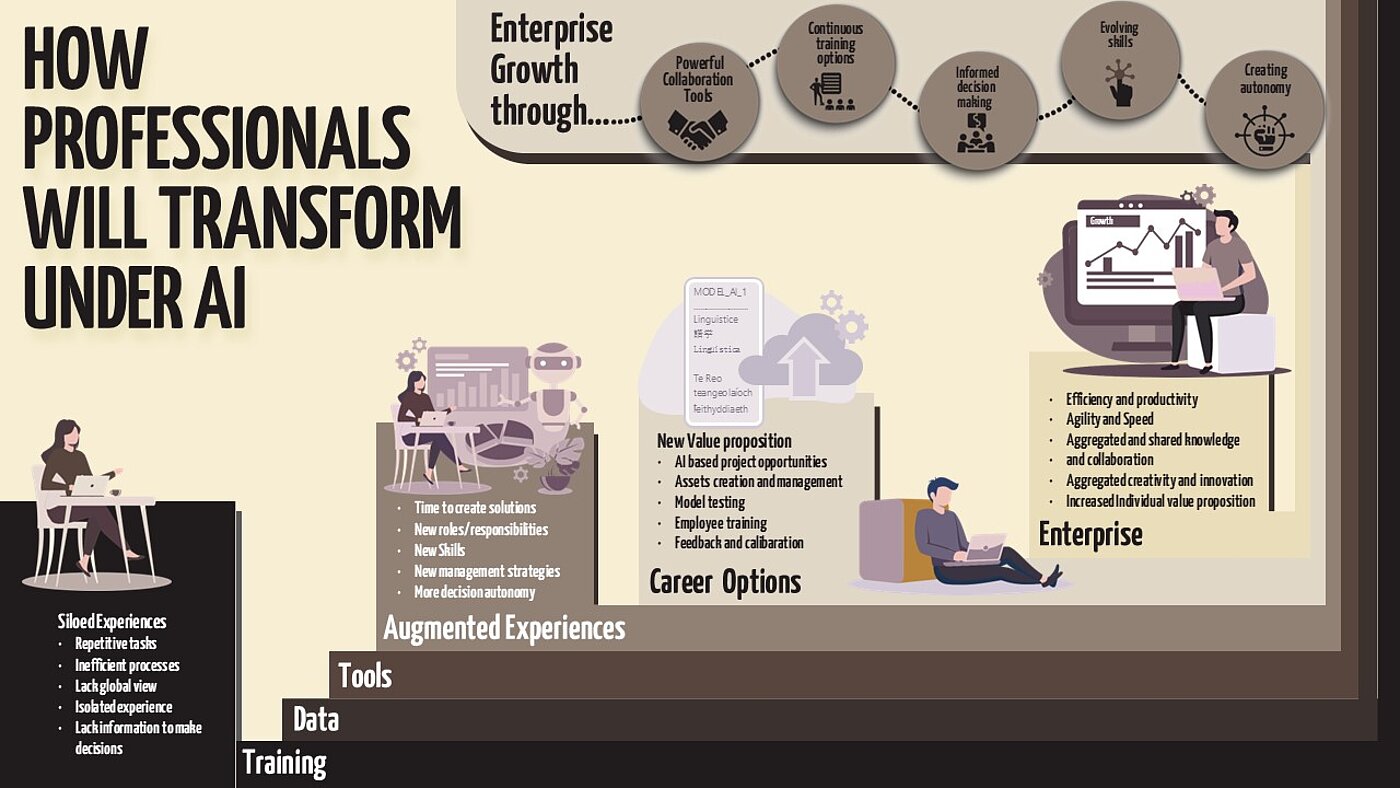

As AI systems and workflows evolve and integrate into business operations, understanding this ecosystem and adding value is essential for professionals. Consequently, this transition is predicated on adaptability and early participation. As localization solutions evolved to address language barriers, equally sophisticated content operations strategies are needed to help tackle content and data barriers. The opportunities are vast.

Engaging in robust, iterative collaborations with stakeholders such as data scientists and developers to support AI outcomes is critical and will reinforce the role of technical writers. A recent Gartner report noted, “At least 30% of generative AI (GenAI) projects will be abandoned after proof of concept by the end of 2025, due to poor data quality, inadequate risk controls, escalating costs, or unclear business value.”

Translators are not just the canary in the mine shaft, but the litmus paper that shapes future progress

- Sinead Healy, Language Services Director TWi

Human oversight

Translators have pioneered the field and ensured that AI-driven translations meet commercial goals. Initially focused on productivity with the "human in the loop" model, they then shifted to a multifaceted asset management role, optimizing MT and identifying "bad" TM data that caused inaccuracies. As "general-purpose" MT performance plateaued, translators and developers focused on customer TMs, integrating them to create domain specificity.

Translators today regularly evaluate MT output to identify mistranslations, grammar issues, and adequacy issues, providing sentence-level scoring for quantitative performance assessments. They also test MT systems across domains to ensure alignment with terminology and industry standards, highlighting areas for improvement and assessing productivity to prove commercial benefits.

In the same vein, technical content professionals may become critical to enterprise AI governance goals. This is evolving with forerunner legislation, such as the 2024 EU AI Act. Particularly, Article 14 on Human Oversight of High-Risk AI Systems states the need “to properly understand the relevant capacities and limitations of the high-risk AI system and be able to duly monitor its operation, including in view of detecting and addressing anomalies, dysfunctions, and unexpected performance.”

Technical content professionals can play a role in the safe deployment of AI by transforming complex technical information into clear, actionable resources for "natural persons to whom human oversight is assigned." They can also address important issues of "automation bias", promoting critical thinking and informed decision-making by promoting "AI literacy". Unlike translators' early adoption of machine translation (MT), technical writers must proactively engage, especially as the EU AI Act considers not only AI creators but, crucially for both industries, the role of “deployers” and, later, although still under consideration, potential liability.

Clearly, human oversight is key in many areas, especially in AI testing. As such, technical content and translation professionals can help increase the credibility of AI deployment, ensuring faster time-to-market, investment protection, and minimizing post-launch adjustments, recalls, or financial and reputational risks. Article 14 of the EU AI Act comes into force in August 2026.

Data governance

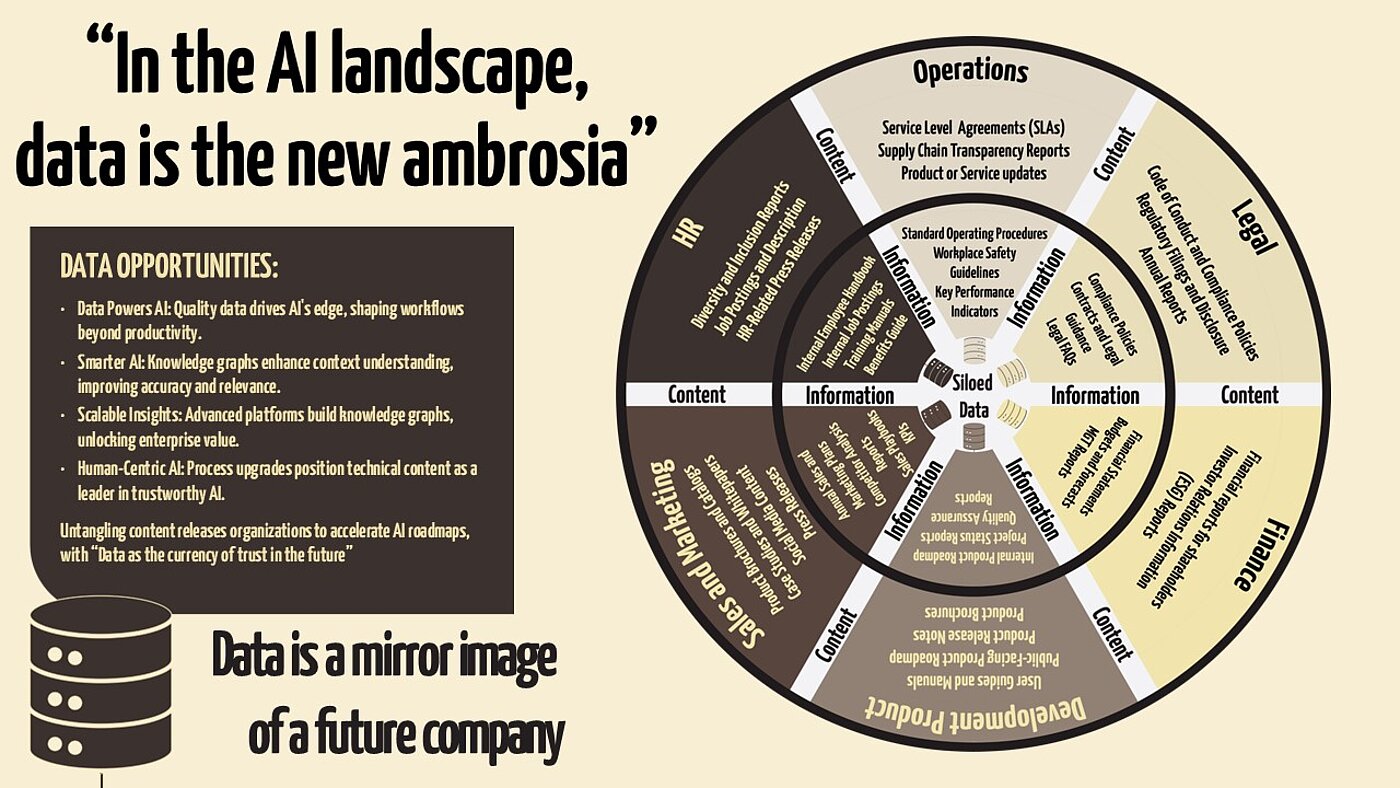

In the evolving AI landscape, data is the new ambrosia. Just as ambrosia gave strength to the gods, quality data powers AI, giving businesses a competitive edge. Localization strategy has evolved from focusing solely on productivity to actively guiding AI across workflow stages. The transition from production to AI stakeholders has been gradual, but technical writers face a very different starting point and pace of adoption.

Today, knowledge graphs, taxonomies, and ontologies enhance RAG systems and address the limitations of general-purpose LLM technology. Knowledge graphs provide structured and discoverable data possibilities, enabling AI models to understand context more accurately and improve the quality of information retrieval. This results in more tailored AI responses to user needs and reduces errors through data cross-referencing, boosting content quality. Sophisticated platform technology now enables the production, at scale, of knowledge graphs that capture relationships between terms, concepts, and content types, improving business insight for enterprise use cases.

Yet, the flow of influence between the technical content and localization worlds is not one-directional. While localization had an early lead in adopting AI-driven processes, technologies like TM have seen their value plateau due to the limitations of their segment-to-segment, XML-based structure. This is despite their interoperability, which is a critical feature for AI tools, systems, and content accessibility. Translators and TM could leverage content specialists' knowledge graph expertise to evolve a more advanced semantic repository, capturing "subatomic" relationships and contexts: Translation Memory 2.0.

Enabling "subatomic context" in localization assets like TM would lead to more relevant translations. Considering the parallel evolution of the localization and technical content industries, this could be seen as a form of reciprocal exchange. Upgrading localization assets may present an opportunity for the technical content industry to position itself as a key AI player, predicated on leveraging human-developed data assets that contribute to trustworthy, human-centric AI workflows.

The “global whole” is greater than the sum of the “local” parts

Establishing a single source of truth for enterprise AI is crucial and may result in new industry convergence and cross-learning. To achieve this, leveraging collective assets such as taxonomies, ontologies, knowledge graphs, and translation memories to create a future multilingual content asset paradigm is key. Using the experience of translators, technical writers can become the “content alchemists” in turning base enterprise assets into AI-ready assets.

However, it is worth noting TM’s value in ensuring interoperability across tools through its TMX (Translation Memory eXchange) standard. This standard cemented TM’s legacy not only in enhancing production efficiency and consistency, but also as a foundational building block for AI language development. As AI workflows emerge, breaking down data silos, it is incumbent not to inadvertently create or neglect new silos or disconnected systems due to a lack of foresight regarding tools, processes, technologies, and expertise.

Let’s make sure that the technical communication industry’s story will one day become an AI blueprint, not a cautionary tale.