There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn’t true;

the other is to refuse to accept what is true.

- Søren Kierkegaard

The truth. Nothing counts more for technical communicators. I could not count the number of times I’ve reiterated to students and colleagues alike, “We write facts, not opinions. We assume nothing, we verify everything.” If you work with heavy machinery or in a regulated industry such as pharmaceuticals, aviation, or medical imaging, you know that accurate technical information can be important to safety, health, and even life itself. The spread of fake news, distributed across social networks and even, sometimes, by societal and political leaders, makes our job more difficult and requires more vigilance than ever to make sure what we communicate to users is not only true, but accepted as true by the users. If we need a reminder of how important this is for our field, we only need to look at the recent COVID pandemic, where we failed effectively to combat the wild rumors that circulated about the disease, its causes, and its treatment.

Fake versus fact

One of the main difficulties in confronting fake news is that it resonates very forcefully with what some people want to believe. In an era where trust in government institutions and the media is at an all-time low (according to the annual Edelman Trust Barometer), starting off with a statement like, “They don’t want you to know this, but…” reinforces the already existing sense of disaffection, and often of anger, that people are feeling. When this gets bounced around the echo chamber of social media algorithms, the effect is amplified exponentially in a very short time. Readers respond to this type of post emotionally – it feeds beliefs, fears, or faith in statements or ideas that have not been demonstrated to be true, but which have a visceral appeal to the state of mind of the reader.

This gut-level circulation of ideas gets out of control almost instantly, like audio feedback when a microphone is too close to a loudspeaker. The French urbanist and philosopher, Paul Virillio, argued that real-time information widely diffused, such as on networks like CNN, removes the reflection and analysis that professional journalists bring to a story. In the same way, social networks where people respond instantly, without taking time for reflection, provide a short circuit for information.

These networks are often referred to, mistakenly, as social “media” – but in fact, they are not at all mediated, and therein lies the problem. A journalist is one kind of mediator. The role of a journalist is to uncover verified facts and to attribute information to reliable sources. The priority for a journalist is on accuracy and dispassionate, critical analysis. This kind of work is necessarily time-shifted – it cannot happen in real time. It therefore also affords the journalist the perspective taken from one step back, rather than that of a simple relater of real-time information, caught up in the moment, without reflection.

A moderator on a social network should be helping participants to do the same thing, by interacting, asking questions, seeking proof of statements, etc. But the people referred to as “moderators” by social networks are, for the most part, fact-checkers. If they deem an assertion to be false, the assertion is removed. From the user’s point of view, this is as instantaneous as the posting of any fake news itself and the responses to it. Not only that, it looks like censorship. The recent trend of social networks to replace moderators with “community notes,” intended as a counterweight to fake news, just accelerates the real-time nature of activity in these networks, and exacerbates the polarizations that occur around certain postings. It also allows “mobs” to deliberately crowd any postings they dislike with such notes in an attempt to get them removed, or at least ignored. This is neither democracy nor free speech.

Clearly, in this environment, truth does not work.

The Covid pandemic was a clear example of how scientific and technical information can be distorted to pose dangers to health. The claims about hydroxychloroquine as a treatment, the continual contradictory assertions about the value of wearing masks, even claims that injecting bleach would prevent the disease, or that vaccines contained nano-computers to give Bill Gates control of peoples’ lives were all tropes that passed on social networks, and that we professionals were almost powerless to rein in. As a result, some people died, and others were more seriously infected by the virus than necessary.

So, how can we combat emotional responses to fake news with cold facts and figures? How do we respond to notions that science is simply “an opinion like any other?” Can we find a way to add emotional load to truth? Should we? Would that solve the problem?

Managing experience

It is my notion that attempting to pile emotional charge into verified truth is ineffective and inefficient. And as strong as emotion may be as a motivating force, it does not lead to confidence building between information sources and information consumers.

Would we want to start writing emotionally loaded warning messages like this one?

⚠️Warning – this product is for external use only. If you swallow it you could die with violent convulsions, so don’t do something stupid!

While it is neither possible nor desirable to turn back the clock in the media environment, we can draw valuable lessons from what we know about information transmission. This will help us to manage information more reliably. The real-time nature of fake news and other misinformation makes it highly experiential. In our world of technical content, the profession of user experience design comes to mind as one that is focused, just exactly, on the idea of creating experiences for users. So why not adapt UX techniques (and others of a similar nature) to the experience of verifying information? Can we use these techniques to make that crucial step back and allow for critical thinking to take place? Can these techniques help people separate fact from opinion? Can it reassure people?

This is a long list of questions, and we don’t have answers to them all, but I have started to explore the idea of using UX techniques as a way to engage users with truth rather than with fake news. At the time of this writing, I have run two workshops to explore this, including one at the 2024 tcworld conference in Stuttgart. Based on audience feedback so far, my impression is that these ideas and techniques can help.

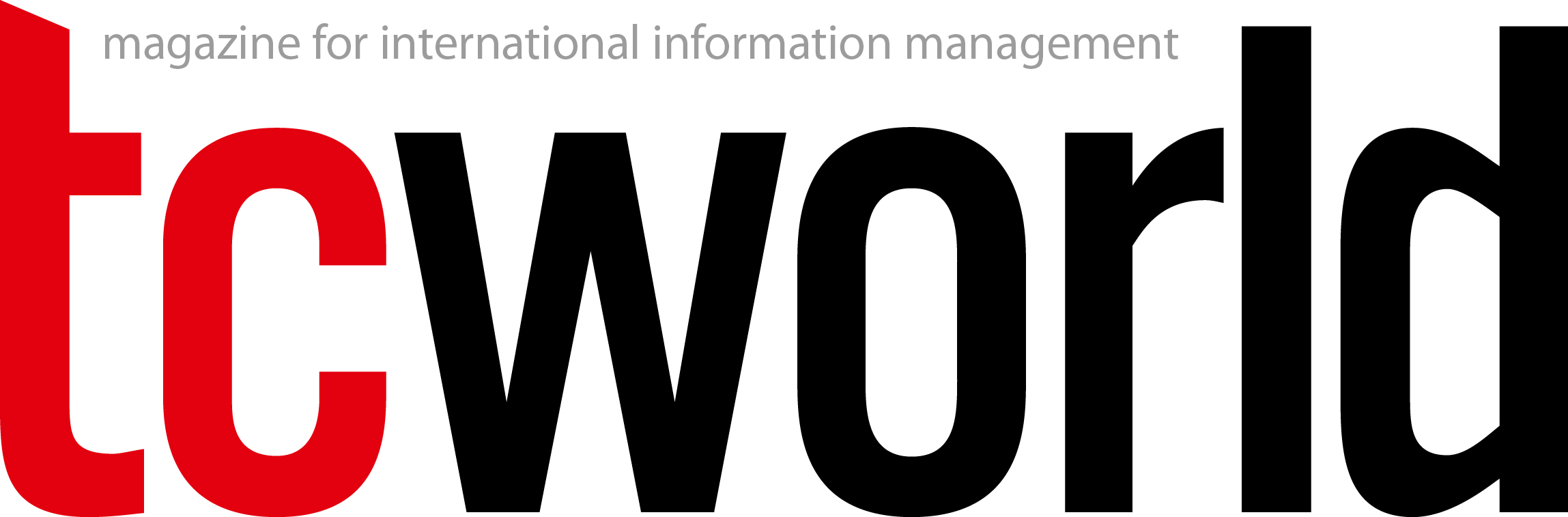

UX explores experiences from both subjective and objective positions, as can be seen in the diagram in Figure 1.

Things to do with users

This is a quick summary of some of the activities that can be run with groups of users in situations where it is crucial to secure their confidence in the face of misinformation.

Inferential learning

Inferential learning is an approach to learning that is based on the idea that human knowledge is abstract, structured, and theory-like – and so cannot be directly copied or transferred. Learning occurs when we interpret the meaning of evidence, but also of others’ behaviors, often based on how the information we receive is generated, and our evaluation of the mental state of the person who is the source of that information. We learn by drawing inferences from observed physical events or self-generated evidence from our own exploration. We also draw inferences from observations and interactions with others, in such a way as to consider their goals, knowledge, and beliefs.

In short, in order to understand something well, we need empirical information, but we also need to exercise our powers to deduce, to infer, from what we observe, to build a complete understanding, and anchor it in memory.

Dr. John C. Carroll, the originator of minimalist technical documentation, favored this kind of learning as we tend to remember things better when we have to figure some of it out ourselves. People have often misunderstood this to mean that information should be deliberately omitted from documentation, but what Dr. Carroll is referring to is, in fact, that we cannot learn only from an objective text, we must infer contexts, consequences, and generalizations of the specific information we receive.

If we step back and take a cool look at who generates a given piece of information, what their goals, knowledge, and beliefs are, and examine this in the light of other things we know, we are more likely to exercise clear judgment on the reliability of what we have received.

Researchers at the Machine Learning Laboratory of Carnegie Mellon University in the United States have produced a guide for reproducible, verified knowledge testing – an experimental method that includes both empirical and inferential learning – that can be useful for technical and scientific information, see Table 1:

Project phase | Empirical | Inferential processes |

Hypothesis | Is the hypothesis definition conceptually and mathematically clear? | Is the hypothesis stated before collecting and analyzing data? Are the necessary tests defined? |

Data collection | Is the sample size adequate to test the hypothesis? Is it unbiased? Is the collection protocol clearly defined? |

|

Data modeling/ | Are all parameters and models clearly and systematically documented? Have you controlled for possible causes of randomness? |

|

Results and interpretations |

| Have you controlled for multiple hypothesis testing? Are conclusions unbiased? Is there an effort made to point out limitations and negative results? |

Reporting | Is the description of methods and results complete and sufficiently detailed? Is data or code open-sourced? | Is the literature review extensive and does it cover all viewpoints? |

Table 1: Empirical and inferential components of scientific investigation, from Carnegie Mellon University

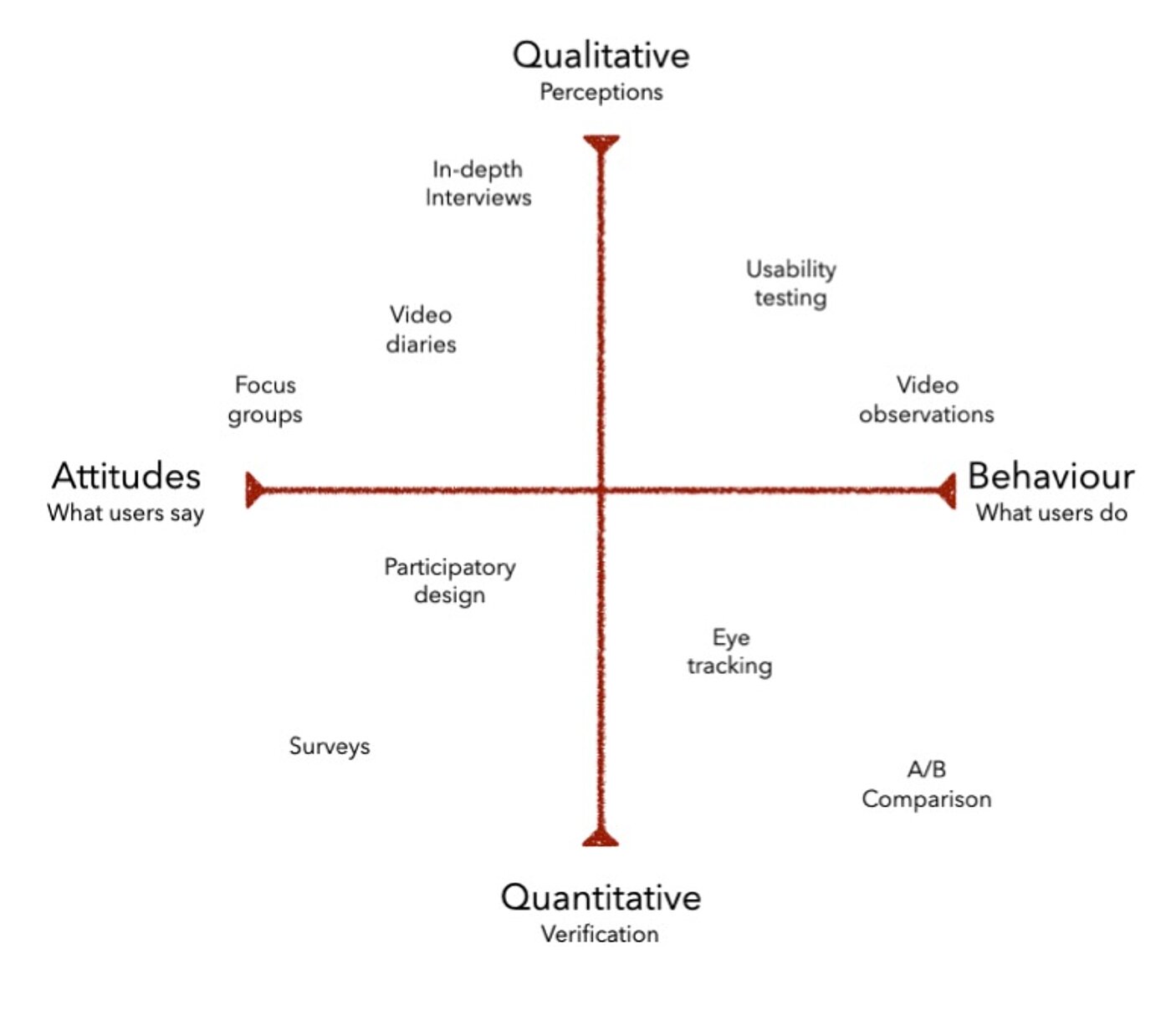

User journey mapping

A user journey map is a visual representation of every stage of engagement users have with our information. By mapping every channel and touch point users have with our content, we can evaluate where we might be vulnerable to misinformation, and can be better prepared to give our users a high-value, verified, reliable information experience. The journey map needs to be created taking the user’s perspective. It should express their expectations at each step, their emotions and concerns, and take into consideration the user’s desired outcome as well as your organization’s desired informational outcome. Figure 2 shows an example of a generic journey map and what can go into it.

Steps for developing an information experience user journey map:

- Outline touchpoints – where do we contact users when they need help?

- Create user personas – who are they?

- Design a typical experience, showing:

- All the phases the user goes through accessing your information (for example, to accomplish a task or to understand a process)

- Emotions they can experience at each phase and when they experience it - Recruit test users

- Execute a trial run – make sure to record all user observations

- Review for accuracy and completeness, most importantly verify the emotions users manifest

- Analyze for improvements and revise

- Add a graphical representation of the journey to training materials, whether for internal team members or users

- Apply what you’ve learned to the content development chain to improve the information experience.

WebQuest

WebQuest is a learning instrument developed by Dr. Bernie Dodge, of San Diego State University, California. It is a mode of study built on principles of educational constructivism, where information is gathered collectively from sources on the Web. It is useful to apply with groups of users who need to be made aware of how to search and verify information in order to improve trust in the information you supply them. A WebQuest is a group activity, and the collaborative aspect is a key part of the discovery process, as consensus cements the understanding of how information is verified. The steps in a WebQuest are as follows:

- Introduction: Understand the nature of the research to be done, define evaluation criteria.

- Task: Define the specific research question to be answered.

- Process: Outlinethe steps users will follow in answering the research question. Users are given hyperlinks to some material to get started. Users must verify the accuracy of the information they discover.

- Evaluation: The evaluationshould be precise, according to specific criteria agreed on before beginning the exercise. Users must justify how they have verified the information they accept or decide to reject.

- Conclusion: The conclusion wraps up the findings in relation to the original research question.

- Sources: Like in an academic paper, sources used in the findings are credited, with URLs and authors.

Example of a WebQuest activity

You are a writer and speaker for a public health agency. There is concern about bird flu spreading to humans and possibly being transmitted from human to human. It’s not a pandemic, but it’s important. A new vaccine has been developed and your job is to help citizens (users) understand its value, but anti-vaxxers are all over social networks spreading fear. Your job is to help a group of non-expert users understand what science knows about the vaccination for bird flu at the present moment, and about vaccinations in general.

You can design a WebQuest for your users to pursue in groups. It doesn’t need to be extensive, and the users can do it in a relatively short time. Afterward, bring several groups together to discuss what they have learned, and to discover if anyone’s opinion has changed (in one direction or the other…).

It might play out like this:

- Introduction: This WebQuest will investigate the validity of arguments for and against the use of the bird flu vaccine. The evaluation will be based on how well the conclusions of the participants are validated by scientific research that has, itself, been validated in the scientific community.

- Research question: Can we establish that the new bird flu vaccine is effective in preventing human infection by the virus, without causing unacceptable side effects?

- Process: Work together in groups of five. Each group will search the Web for information about the bird flu vaccine. When you find information that you agree is of interest, find out its source: Where did it come from? Is the source reputable? Has it been validated by others in the scientific community? What criteria have you used to decide the validity of the source?

You need to find at least three independent sources to defend your answer to the research question. Make sure you can prove that the sources really are independent. Many times, sources that appear to be independent have gotten their information from a common source, so research thoroughly.

Here are some URLs to get you started – you need to go beyond these to successfully complete the WebQuest. Develop search strategies that you can use and document them in a few words. xxyyyyy.edu, xxyyyyy.com, xxyyyyy.info - Evaluation: How did you arrive at your conclusions? Do the conclusions meet the criteria you set up at the beginning? Justify how you have verified the information you have accepted or decided to reject.

- Conclusion: What is your answer to the research question? Have your ideas been changed or reinforced by this process?

- Sources: Provide a list of sources you consulted, including URLs.

Card sorting plus interviews

Card sorting is a tried-and-true UX technique that can help design the layout and content of user interfaces. When using it to identify fake news, users are presented with a deck of index cards, each containing one assertion relative to the subject. In groups, users decide which cards are definitely true, which ones are definitely false, and then create a scale of categories in between for the rest of the cards. Users are free to create as many categories as they think they need, or none at all if none are needed.

The card sorting itself helps to understand the group of users rather than producing hard results. Users learn how others in their cohort organize information, which can be valuable insights for us as professionals. This may lead us (and them) to question our assumptions. The process of sorting, the group debate and discussion can actually be the most interesting part of the process, acting almost like a focus group, from which you can learn more about attitudes and understandings than you can from the actual card placement. For this reason, when you do a card sorting exercise, it is useful to assign one or two group members as observers. Observers do not participate in the sorting process, but record important points of discussion, for example:

- Are there people in the group who can be singled out as more important “influencers” than other group members?

- What kinds of sources are cited in the discussion, and what else backs up the arguments?

- How is a consensus reached?

- What questions would you want to ask in a follow-up interview?

Indeed, follow-up interviews with group members can be a valuable source of information about the attitudes, beliefs, and values of users and how they make decisions about truth. The questioning process itself may also have some impact on users’ thinking. Depending on the outcomes you are seeking, there are several categories of questions you might use:

- Questions to elicit information:

- Closed questions: facts, yes/no answers (will you, can you, what is…)

- Open questions: how, why, for whom, tell me about…

- Choice questions: do you want this or that?

- Questions to show interest, or go further:

- Reformulation of the same question

- Repetition of the answer: not really a question, but stimulates the production of more information

- Motivational questions: with your great experience, how would you…

- Questions to verify information:

- Interrogative questions: what did you mean?

- Control questions: so, we agree that… right?

- Reformulation to confirm meaning.

A three-level problem

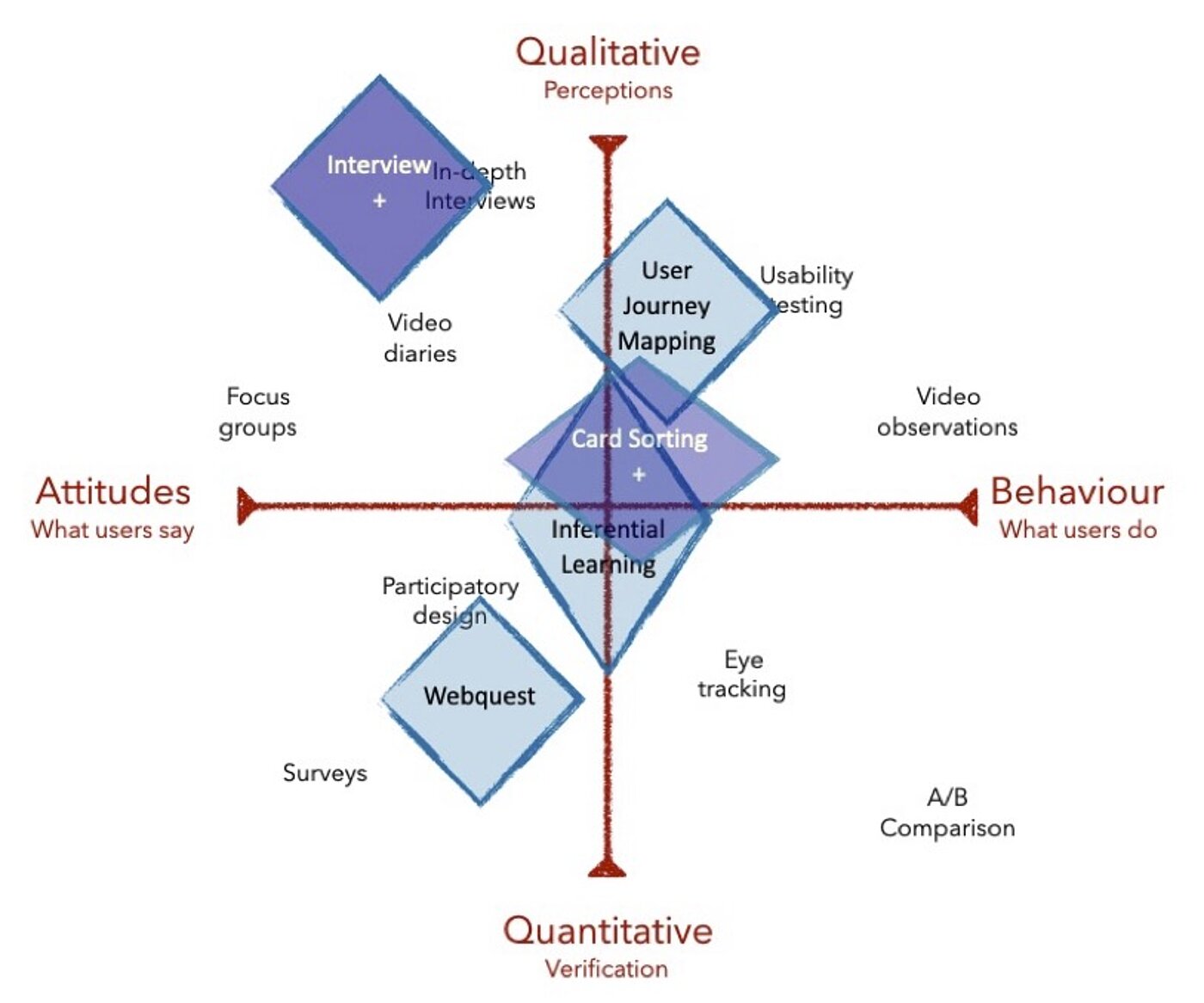

All the techniques described above can be mapped onto the sphere of UX techniques as shown in Figure 3. It should be clear that most of these techniques remain in the qualitative domain, and many of them also work on users’ attitudes. That is to say that we are still very much working in a subjective domain, even though our subject is to determine what is true, and what are facts.

In the struggle to build trust and conquer fear, we content professionals have a major role to play, and it seems clear that we can harness our professional techniques to help do this effectively.

Further reading

- Edelman, Trust Barometer, https://www.edelman.co.uk/research

- Hyowon Gweon, Inferential social learning: cognitive foundations of human social learning and teaching, in Trends in Cognitive Science, Volume 25 Issue 10, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1364661321001789

- Serhat Kurt, WebQuest: An Inquiry-oriented Approach in Learning, https://educationaltechnology.net/webquest-an-inquiry-oriented-approach-in-learning/

- Donna Spencer, Card Sorting: designing usable categories, Rosenfeld, 2009

- Paul Virillio, Desert Screen: War at the Speed of Light, Continuum, 2025

- Paul Virillio, Politics of the Very Worst, Semiotext, 1999