At a recent conference, I was challenged by the organizers to address a very specific question: What happens when one of our most important audiences isn’t human? What if one of our readers is a machine, an Artificial Intelligence (AI) agent? It was a good question because it reflects an inescapable reality for all technical writers, indeed for all authors. This article explores this question and tries to paint a picture of what lies ahead in the future of technical publishing.

How did we get here?

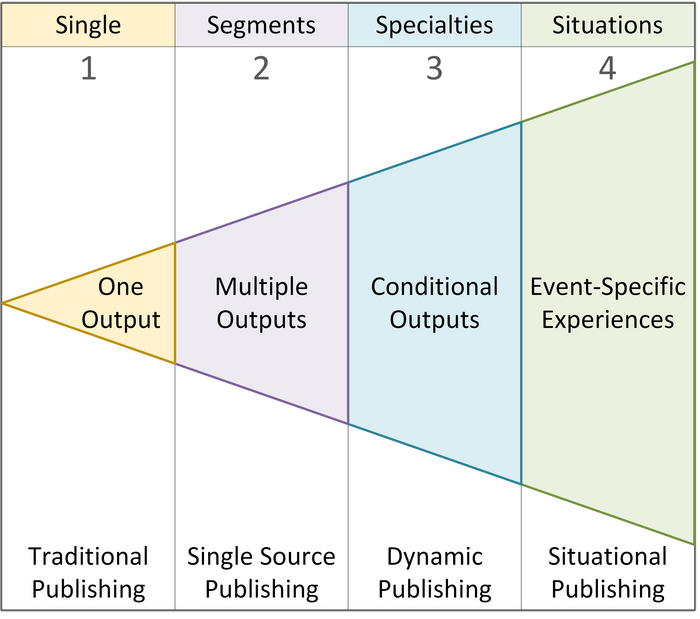

Let’s jump right in and think about how technical publishing has evolved over the last 30 or so years. As can be seen in Figure 1, I have divided this history into four modes or levels:

- Traditional Publishing

In this mode, a single product is typically produced, and its contents are usually inseparable from the format that is applied. Think of printed manuals, for example. In this mode, all users are treated the same. - Single-source Publishing

This mode emerged in the 1980s and reflected the need to publish content in more than one format to address the demands of specific user segments. Initially, it was print combined with some form of digital delivery. A little later, the Web was introduced and quickly became a dominant delivery channel. It was this need to address multiple publishing channels that forced communicators to look more closely at the content itself as something distinct from and shared across each of the channels. - Dynamic Publishing

This mode responded to the increasing number of product variants as well as to the new capabilities offered by evolving digital channels. This level represented a significant change because the conditionality of information being provided was too numerous to be efficiently addressed in advance. As a consequence, this mode has depended on the dynamic generation of publications to address the mix of conditions that would apply to specific product configurations and user roles. As a response, this gave rise to database-driven content delivery platforms. - Situational Publishing

This is the mode that represents the future of technical publishing. In this mode, published information products are not only personalized to an individual, they are customized for the specific situation in which that individual is working. The number of variables in play is so great that they simply cannot be established beforehand. In many circumstances, the number of variables is quite literally infinite. This is where AI plays a vital role in mediating access to, and the consumption of, technical information.

This four-part breakdown of publishing models lines up nicely with the four industrial stages of Industry 4.0. As with Industry 4.0, each new level brings with it both efficiencies and challenges. The challenges include increasing sophistication and complexity, for which increasing design maturity is the main response. When we consider publishing itself, we are forced to concede that the technologies and techniques available to, and utilized by, technical communication groups have struggled to keep up. Consequently, technical communicators and their management stakeholders have felt squeezed between the escalating demands for situationally specific information experiences and the hard realities of creating, managing, and publishing good quality technical content.

The recognition of this situation is not new. As far back as 1993, a technical communication team from the United States Air Force (USAF) provided a dramatic illustration of how complex modern systems were becoming. At a conference in San Antonio, Texas, this USAF team rolled a very long scroll of paper down the central aisle of a large conference hall. It contained a single diagnostic procedure on an electrical component of a state-of-the-art aircraft. Their point was that this was unsustainable. There were simply too many possible diagnostic situations to document them all in advance. Their recommendation, in 1993 and which now seems prophetic, was that we would need to deploy AI.

The contention that this paper is putting forward is that AI is an essential part of any sustainable response to the demands associated with situational publishing. As we must accept that these demands are inescapable, we must also accept that engaging with, gaining control of, and building on the value of AI is mandatory. Our technical content ecosystems will depend on it.

The roles of AI today

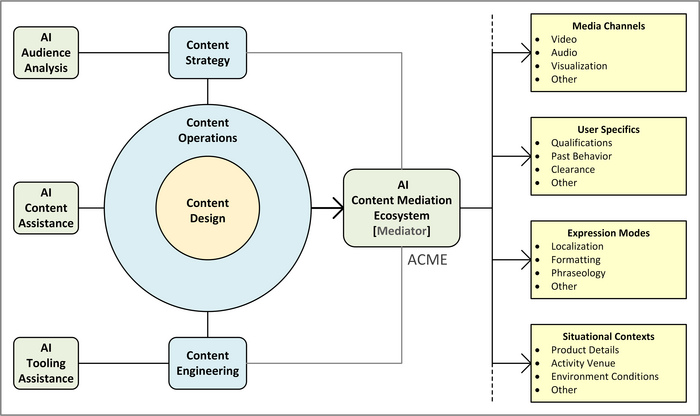

Figure 2 identifies some of the important roles that AI can assume within a technical content ecosystem.

We can look briefly at each of the roles illustrated here, focusing in the end on the one that can be endorsed as the most important – the AI Content Mediation Environment.

- AI Audience Analysis

This use of AI builds naturally on practices that have emerged around user analytics. These practices have been stronger around marketing communications historically, but with the availability of AI, it can become a more widespread practice within technical communications. By gaining a more refined understanding of your audiences and the challenges that they face, technical communicators will be in a much better position to prioritize content investments that have the biggest positive impact. - AI Content Assistance

This use of AI has been receiving a fair amount of attention within the international community of technical communicators. And it is not difficult to see why if we recall the pressures technical communication professionals are feeling and the challenges they are facing. Here, AI is enlisted to facilitate the creation and refinement of content assets and then used to enrich those assets with metadata that can concretely improve the discoverability of the published information resources. - AI Tooling Assistance

Receiving comparatively less attention is the role of AI in supporting the technology infrastructure needed by the content ecosystem. This reduced amount of attention will change rapidly as organizations discover that more esoteric tools and standards associated with content technologies can be effectively managed using AI. This change, along with others that we can expect to see in response to the growing reliance on AI, will see content technologies become more mainstream, or at least more accessible from the mainstream of technology practice. - AI Content Mediation Environment

While each of the uses of AI touched on in this diagram is important, the role of mediation is the most important in terms of its impact on technical publishing. Here, AI becomes the main audience for the technical content being produced, and it acts as the mediator between that content and all the potential human audiences that may exist and all the situations that those audiences may find themselves in. In this diagram, the name for this use of AI is ACME. While this acronym often refers to a generic product or company, such as is seen in cartoons, in Greek it refers to the pinnacle or peak of something, its highest manifestation. This acronym is intended to emphasize the importance of the role being played here by AI as the mediator that allows content teams to produce a single, clear representation of the content and to have the AI content mediation environment address all potential access and interaction scenarios.

The right-hand side of Figure 2 attempts to depict the fact that the AI content mediation environment could, in principle, address an unlimited array of variations. This could include, for example, adapting the language being used in the source content to align with a specific reading style. This might be helpful when some of the content is used in a marketing context, where the language should ideally be more informal. As another example, and this is a rather obvious one, it could include translating the content into the language of the user.

As a more practical scenario, when we are considering product information, the AI content mediator could be engaged in selecting components of the content and presenting them in a way that helps an equipment maintainer to address a very specific problem in very specific environmental conditions and drawing on very specific real-time data sources. Perhaps in this latter scenario, the equipment maintainer requests that the assembled procedure be delivered through a combination of audio, video, and step-by-step procedures projected directly into an augmented reality interface. The AI content mediation service can do that. In this scenario, we can see how the content assets being drawn upon by the AI mediation service would be used in concert with a structured metadata set that is partially populated from the content and partially constructed from a variety of external data sources, including component suppliers. In this scenario, the AI content mediation service would dynamically tap into and leverage metadata resources using the Intelligent Information Request and Delivery (iiRDS) standard. With the AI content mediation environment (ACME), the content assets that technical communicators work so hard to plan, create, and manage become a fully active part of a future-state product information experience. These futuristic experiences will be leveraged throughout the modern digital product lifecycle, including design, manufacturing, assembly, integration, operation, and maintenance.

So, what lies ahead

This article commenced with a deceptively simple question: “Who are you talking to?” As we have seen, this is anything but a simple question now that AI is in the picture. In many circles, technical communicators are wrestling with other questions, such as how their work will be impacted by AI. What we have explored in this article is the fact that AI can play a variety of roles in assisting the content ecosystem and lifecycle. In particular, AI can mediate between a core representation of a product’s content assets and all the variations that its many audiences and audience situations can call for. Interestingly, this puts the focus not on AI itself, but on the core content assets that technical communicators produce, even if they use AI in many ways to assist them. It puts the focus on the content itself, its quality, and its ability to instruct and guide the behavior of the AI services used across the content ecosystem and lifecycle. It puts the spotlight on good content – content that is clear, curated, credible, and compelling. Good content informs its audience, guides their behavior, and motivates them to act in specific ways. It is not at all clear that AI can do this part. Indeed, a strong case can be made that AI alone cannot produce good content. However, experience has shown and continues to show that as the AI infrastructure accelerates in its evolution, the one thing that AI needs to deliver highly effective information experiences is the good content that people – working together and balancing a variety of considerations – can produce.

It may sound simplistic and perhaps even self-serving, but once technical communicators adapt their working practices to the new realities that AI has introduced, they discover that they will have more work to do in the future, not less. Given the future of technical publishing that we have explored, their value will only increase exponentially with the reach that AI provides them.