In our article “UI strings: Don’t let inconsistencies derail your user experience”, featured in tcworld magazine in January 2025, we presented best practices for maintaining the words on a user interface (UI), a.k.a. UI strings. In this follow-up article, we highlight the importance of consistent wording on the UI and in the user documentation for a complete and cohesive user experience (UX).

This article describes a method that has been successfully implemented by two teams to align UI strings between software and documentation.

The mismatch you didn’t mean to write

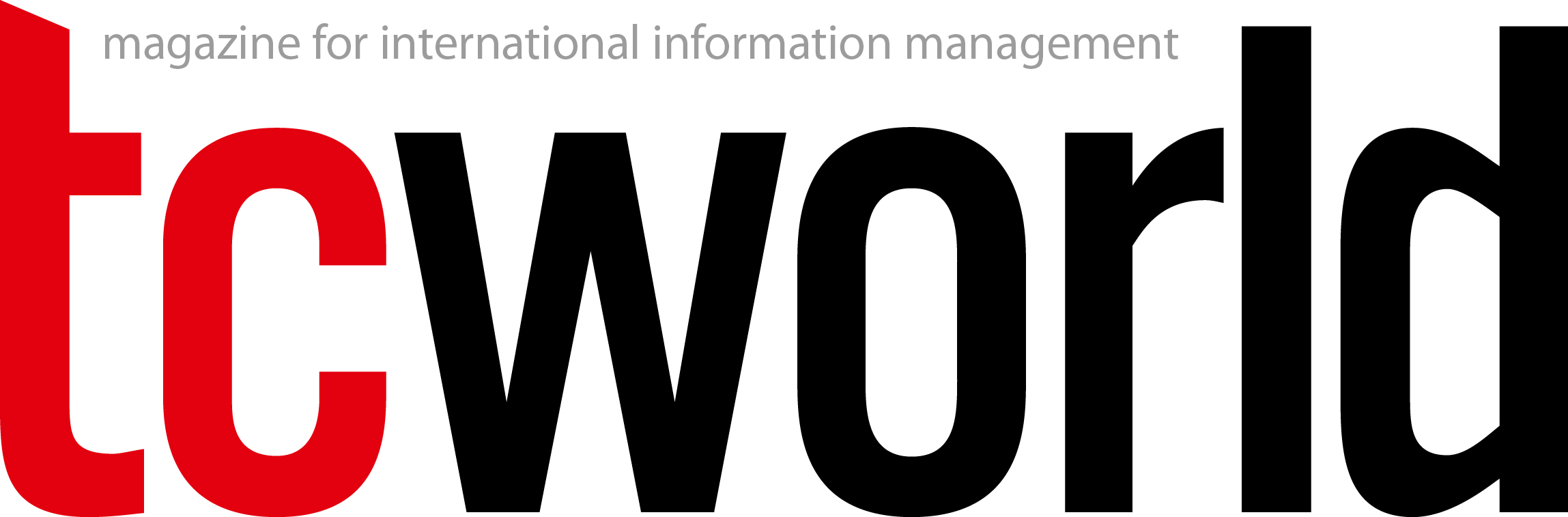

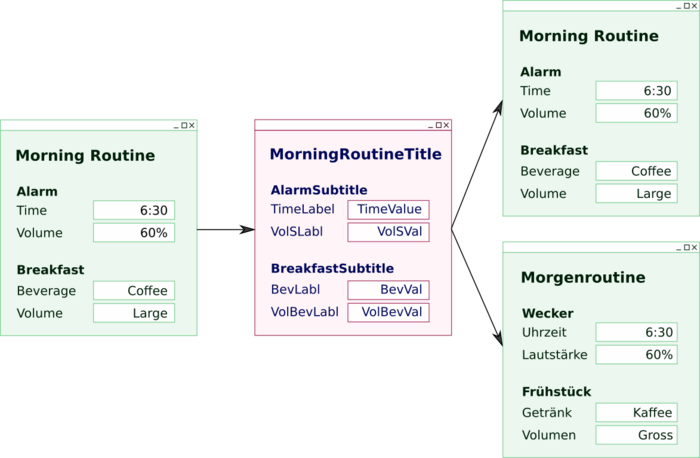

Imagine a user manual instructing the user to "Configure the size of the beverage using the parameter Size" (2) while the UI displays only a parameter labeled "Volume" (1), see Figure 1.

Clearly, our user documentation is only useful if the strings used on the UI, such as buttons, menus, etc., are consistent with those used in the documentation. You might assume that defining the UI strings early in the software project will prevent such issues. However, changes might occur right before publishing or with later releases. Inconsistencies often arise when a UI string is updated in the software, but not in the documentation. On other occasions, the strings used in the documentation are translated with the documentation content, while the UI is translated separately and a synonym is used to translate the specific string. For example, Figure 1 shows "Volume" translated to German as "Volumen" in the UI (3), but as "Menge" (4) in the documentation. While both terms are valid, instructing users to select an option that does not exist in the UI can be confusing and frustrating.

Some of these translation problems can be alleviated if UI strings are semantically tagged in the documentation, indicating to translators that the translation of these elements needs to be aligned with the UI. However, this manual tagging process is both time-consuming and error-prone. Technical writers need a systematic approach to ensure that the strings used in the documentation are consistent with those published in the UI.

A process for consistency

The method suggested here uses placeholders to ensure that UI strings in the documentation match those on the UI, across releases and languages. The documentation benefits from this approach in both the source language and the translated languages.

What are "placeholders"?

Most component content management systems (CCMSs) offer a feature that allows the use of placeholders in the text, which are replaced with the corresponding content during production. Depending on the software and XML standard in use, these placeholders might be called variables, keys, metadata, or data nodes. In this article, the generic term "placeholder" is used.

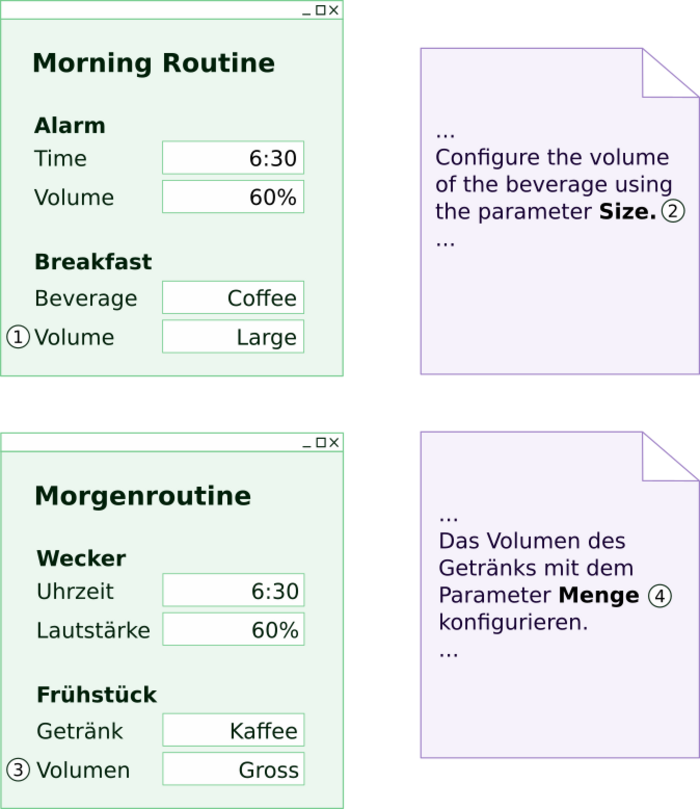

The main idea is to encapsulate each UI string in a placeholder that is assigned a unique ID or key (referred to here as "string key"). During production in a specific language, each placeholder is automatically replaced with the UI string in that language (see Figure 2).

Placeholders include any complete string from the UI: text on a button, window title, tooltip, etc. They can include a single word, such as “Accept”, or up to several paragraphs, such as error messages.

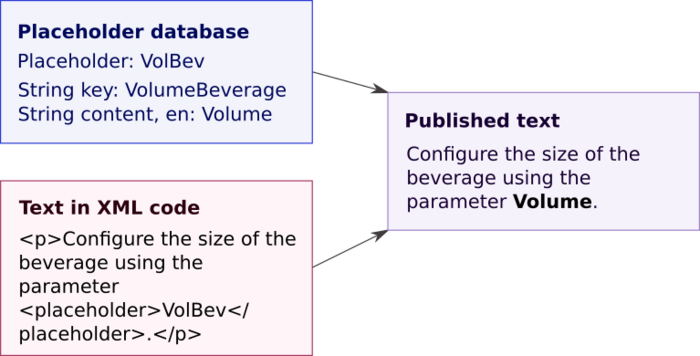

Using the same unique string keys for both the UI code and the CCMS, as shown in Figure 3, creates a direct link between the UI and the documentation. This is the cornerstone of the process presented here.

Collaboration: the key to consistency

With the use of placeholders in user documentation, UI strings become a shared resource between software engineers and technical writers. As a result, the two teams need to define how to manage this resource collaboratively.

Let’s take a look at three major challenges that might arise from this multidisciplinary collaboration and how to address them.

Tools setup

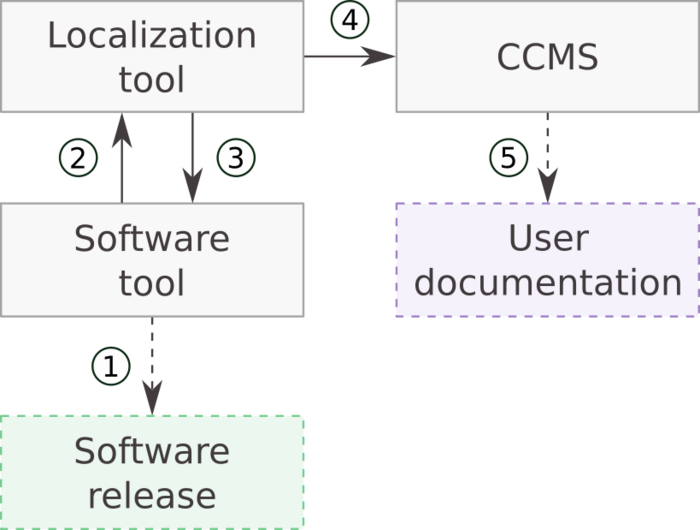

UI strings are not only shared across teams but also across multiple tools. The specific tools involved vary for each company and project. In this article, we use the setup shown in Figure 4 to illustrate the key challenges to be addressed. This setup involves three types of tools:

- Software tool: Used to create the software code and generate the software release (1). String keys are created in the software tool and exported to the localization tool (2), where the content is managed.

- Localization tool: Manages the content and translation of the UI strings. The content is exported for use in both the software tool (3) and the CCMS (4).

- CCMS: Used to create and publish user documentation (5). Placeholders are created and managed in this tool.

Challenge 1: Synchronization of timelines

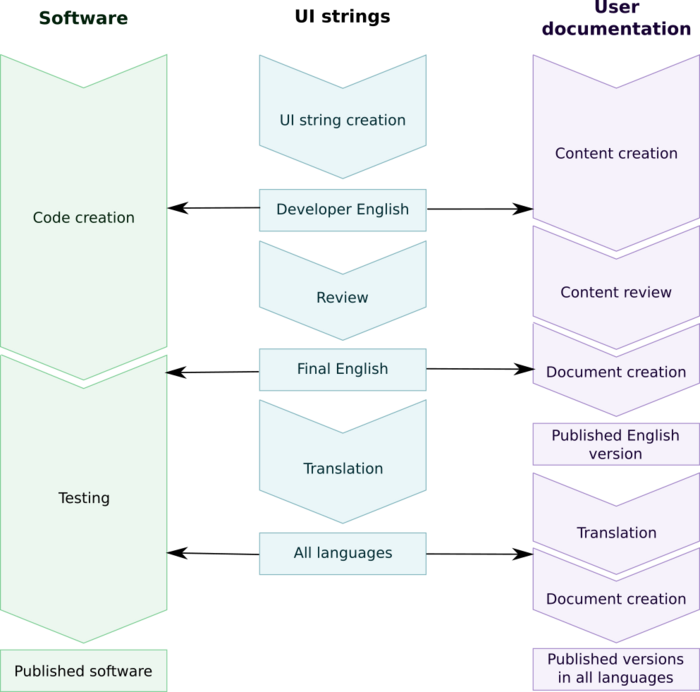

The timelines of software development and user documentation are linked, yet they rarely align at key stages, and both are influenced by the timeline of the UI strings. Figure 5 shows these three timelines side by side.

Typically, the software architect includes text in the mockup screens when developing the architecture. Ideally, these strings are reviewed and finalized before they are implemented in the code. In practice, however, they are often changed later in the process. In addition, UI strings should not be the sole responsibility of the software engineer. Engineers need some strings in order to render and test the UI, and technical writers need UI string content – even temporary – to render and test the documentation.

To support both needs, the UI strings are created with temporary English content, known as "developer English". In the translation tool, this content is "translated" into "final English", which serves as the source for the translation into other languages. Managing the UI strings separately from software and documentation, as well as applying this two-step translation process, has several advantages:

- The UI strings content is available early in the development process.

- The English strings can be reviewed and refined without editing the source code.

- The independent management of UI strings breaks the direct dependency between software and documentation timelines.

For user documentation, translation and publication can begin once the final English version is available. These steps can add a lead time of several weeks, often longer than the software lead time. As a result, technical writers frequently need the final English and translated UI strings before software engineers do. These varying requirements of the two teams on the UI strings must be analyzed and discussed across teams.

Challenge 2: Data exchange

Technical writers need the following data to create and maintain placeholders:

- String key: A unique identifier used to synchronize placeholder content with the corresponding UI string. To ensure successful synchronization, string keys must be unique and remain unchanged.

- String content for each language: The actual text that will appear in the user documentation for each language.

- Context information: Data that distinguishes between UI strings with identical content but different meaning. For example, "volume" can describe the quantity of a beverage or the loudness of a sound (see Figure 3).

This data can be exported from the localization tool. It is essential that the exported data is in a format compatible with the CCMS, allowing seamless import. The import process relies on a mapping mechanism, where the string key is used to identify the correct placeholder, and the other information is mapped to the placeholder's metadata or content fields. This mapping works only if the structure of the exported data is defined and remains unchanged.

Working with placeholders is usually an iterative process.

- First iteration: An initial set of placeholders is created, including the string key, developer English, and context information.

- Subsequent iterations: Placeholders for new UI strings are added, and the developer English is replaced with the final English. Before publishing the English user documentation, all placeholders must be available and updated with the final English content.

- Final iteration: Before translated user documentation is created, placeholders are updated with the translated UI strings.

Because of the iterative nature of the process, it is critical that the string keys do not change. However, there will always be exceptional cases where it makes sense to change the string key. For example, if the terminology of a key feature changes, it might make sense for the string key to reflect the new terminology. The software development team needs to be aware of the impact of such a change on the technical writing team.

Challenge 3: Fostering a common understanding

As we have shown in the previous two sections, coordination and collaboration are essential to making placeholders work. Even with well-defined processes in place, success depends on all teams following them and being able to handle unexpected issues that inevitably arise during a project. When all stakeholders have a basic understanding of each other's needs, they are more likely to adhere to processes and respond flexibly to unforeseen problems.

Software engineers create UI strings and assign string keys. They need to understand how their actions impact the work of technical writers. As a technical writer, you can take the following steps to help foster a common understanding with the software team:

- Explain how placeholders work.

- Present and justify your requirements.

- Provide concrete examples of what can go wrong when the process is not followed, for example, the consequences of changing a string key.

- Designate experts on both sides to align needs and act as points of contact when issues arise.

With a shared understanding, both teams can jointly define a process for managing the shared resource. This process should also include instructions on how to handle exceptions, such as when a string key must be changed. Having designated contacts helps streamline communication and resolve unexpected issues efficiently.

Leveraging placeholders in the documentation

Placeholders can be used in text as well as in screenshots.

Placeholders in text

Using the placeholders in the text offers several advantages:

- Single source: If the UI string content is updated at the source, all instances in the document are updated automatically.

- No impact on translation: The content of placeholders can be updated without triggering the translation workflow.

- Consistent translation: The UI strings remain aligned between the source and all translated languages.

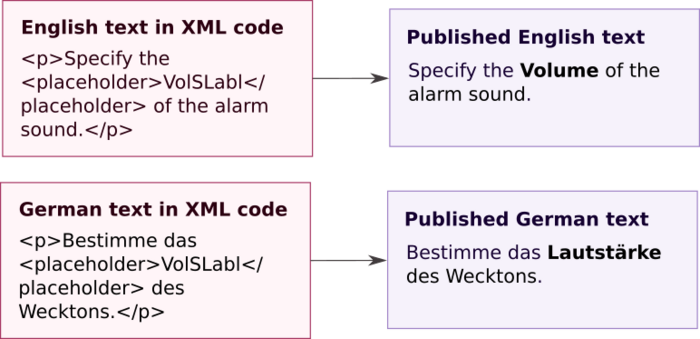

However, using placeholders in running text also comes with risks. When used this way, the UI strings are encapsulated in XML code. Their content might not be visible to the translator, who may then struggle to build a grammatically correct sentence.

Figure 6a shows the XML code visible to the translator when a placeholder is used for the UI string "Volume". In German, the translator must add an article before the noun "<placeholder>". If they guess correctly that the term is "Lautstärke", they might choose the correct article "die". But since the "<placeholder>" does not reveal its actual content, the translator can only guess, making grammatical errors likely, such as using "das" in Figure 6a.

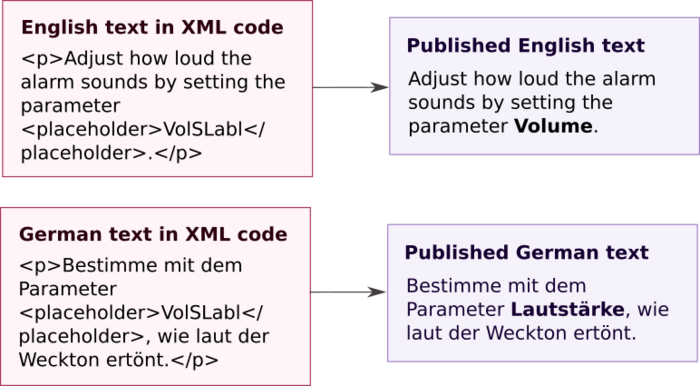

To avoid this problem, technical writers should never use articles, adjectives, or pronouns directly tied to placeholders. Instead, refer to those elements as a "parameter", "setting", or "option", so the surrounding grammar applies to those words, as shown in Figure 6b.

Leveraging the placeholders for the screenshots

One time-consuming step in software documentation is preparing screenshots in all supported languages. Those screenshots often need to be redone for each release due to changes in the UI. The significant effort involved often causes documentation teams to limit the number of screenshots, which can reduce the clarity of the documentation. Additionally, screenshots can only be created after the software is released and the strings are translated, adding another variable to an already complex timeline.

Placeholders can change the way you use screenshots in documentation. There are two common approaches:

- Replicate the entire screenshot for each language.

- Reconstruct a language-neutral screenshot with separate layers for the graphical part and the text part (see Figure 7).

The reconstructed screenshot is language-neutral because the graphical background is the same for all languages, and the CCMS replaces the placeholders with the content of the corresponding string ID in the specific language. This method requires the CCMS to be able to handle composite graphics, i.e., graphics that are composed of one image and several text boxes, whose content is taken from the placeholders.

The first approach takes less time for a single screenshot, but needs to be repeated manually for each language. The second approach requires more effort when creating the content in the source language, but it scales much better as the number of supported languages grows. Language-specific screenshots are generated automatically when producing the documentation, saving time in the long run. Additionally, if the content of a UI string changes in any language in a subsequent software release, the screenshots are updated automatically. This not only saves time but also improves consistency and quality.

Conclusion

Optimizing user experience often feels like the search for the holy grail: frequently discussed but rarely achieved. Generating software documentation that aligns consistently with the UI brings you one step closer to improving UX. While coordination and collaboration between the software development and technical writing teams can be challenging, it is essential. The strategies of working with placeholders presented in this article are tool-agnostic and can be adapted to various environments, likely including your own!